|

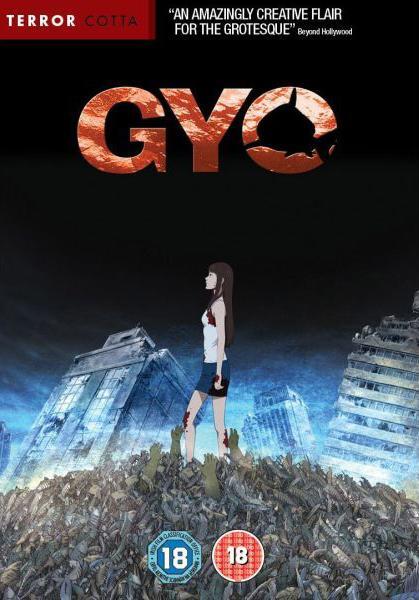

| From http://pics.filmaffinity.com/Gyo_Tokyo_Fish_ Attack-420136789-large.jpg |

Director: Takayuki Hirao

Screenplay: Akihiro Yoshida,

Takayuki Hirao

Based on a manga by Junji Ito

Voice Cast: Mirai Kataoka (as

Kaori); Ami Taniguchi (as Erika); Hideki Abe (as Shirakawa); Hiroshi Okazaki

(as Professor Koyanagi); Masami Saeki (as Aki); Takuma Negishi (as Tadashi)

Viewed in Japanese with English Subtitles

This is the second anime based on

the work of a legendary horror manga author I've covered. The first was (entry

#8) The Curse of Kazuo Umezu (1990) which

is based on the work of the titular man who is as known for his obsession with

red and white stripes as he is chilling readers' blood. In Umezu's case I've

unfortunately yet to read his work as of this review's date of publishing, but

the author of Gyo, Junji Ito, is someone I've been

pleasantly (or is that unpleasantly?) introduced to thanks to the recent reprinting

of his work from Viz Media within the

last year or so. Ito is a unique

voice, both with his trademark drawing style and his storytelling; the fact

that, early into publishing his work again, Viz

have even released his autobiographical story about raising cats means that, if

his work does well, we will hopefully get the likes of his uber popular Tomie stories in the future1.

A bold characteristic of his

horror stories is that, while he does use various tones to his story ideas, he

does tap a great deal into cosmic horror, the same type of horror of mankind

being in the dark with the scope of the universe that was cemented by the tales

of HP Lovecraft. Uzumaki (1998-9), his most well known story including its 2000 live

action adaptation for film by Higunchinsky,

is entirely Lovecraftian; even though its premise is uniquely strange to Ito, about spirals terrorising a small

town to the point they transform both flesh and reality for all those trapped

within the local area, the story especially with what wasn't filmed in the live

action movie evoked entirely the psycho-mythological horrors of a Lovecraft work like At The Mountains of Madness (1931). The monsters and beings that

terrorise the living in Ito's work,

from what I've been able to access with the new Viz Media releases, usually exist outside the rational minds of

human beings even if they are ghosts, the kind of irrational terrors that Lovecraft specialised in. Gyo evokes both Lovecraft's Dagon (1919)

and the nautical horrors of William Hope

Hodgson and while its premise is ridiculous on the surface - dead fish with

mechanical legs, thus proving there's something worse than Jaws when a shark can walk on land - the result is creepy,

legitimately disgusting in its obsession with decay and putrid rotting. With

both the manga and the animated film there's an appropriately apocalyptic tone

where the fish march out of Okinawa and eventually take over Tokyo, Japan and

likely the world.

The adaptation is not as good as

the manga, but it succeeds (pun not intended) on its own legs despite some

flaws by managing to perfectly capture the story's central idea. The film

succeeds in creating an end of the world scenario that admits how absurd it is

but is still gross inducing horror, the fish monsters the result of a gas (and

bacteria within it) that if it infects a host - aquatic, animal, human - turns

them into a bloated gas bag, the machinery on them a gas powered entity which

combines to create horrific bio-mechanical creations to overwhelm modern

Japanese motorways and streets. A pinch of salt has to be taken that a premise

like this which involves bodily gases as a main plot point could evoke giggles

or merely gross people out without the inducing of horror, but horror is as

much a genre to deal with that which is considered inappropriate to discuss in

ordinary conversation - disease and illness even if it contains aspects that

may be unintentionally funny, like farting, are still potentially distressing. Revulsion

is still a powerful emotion to induce especially as the body is still seen as

taboo in certain bodily functions to this day, so the disgust the story induces

is appropriately required as the horror of death. The rotting of a living

person from man to schoolgirl, when its revealed later in the plot, leads to the

bacteria turning their skin almost frog green as gas comes out of every orifice,

still distressing when witnessed animated, more so when the human body meets machinery,

tubes going into places they dare not go and the mix of black humour, disgust

and sight of things one feel shouldn't be depicted out of politeness makes this

a potent cocktail2. In a slight spoiler that you can skip to the end

of the paragraph about if need be, the mechanical legs as well are revealed to

have been a creation of the Japanese military in World War II to harness the

gas as a biological weapon, the premise upturning the habit of Japanese horror

and sci-fi reflecting their monsters through the American involvement in the

war with a creation the fault of the Japanese themselves on the future

generation. As well, this is a tale of nature eventually overruling mankind,

something as absurd as fish land inspired the more you think about it; one, if you

see the dead eyes of fish heads on food stores, there is something unsettling

about the appearance of fish in terms of their appearance especially as

something we kill in thousands and eat; two, the absrudity of the idea, while

in danger of not being scary to some, is more original than another vampire or

zombie as, while the resulting fish are technically undead zombies themselves,

they reflect the idea of anything being dangerous, especially as like zombies

they are dangerous on mass; and finally three, back to Hodgson and sailor's tales of yore, the ocean is a place which

holds danger for human beings, not only covering most of the Earth but a place

with legends of giant octopus, (one such creature appearing in the anime),

white whales which destroy ships, and real life creatures that are poisonous or

accidentally confused humans for seals and rip pieces out of them.

The film changes plot points. A

major one is switching the protagonist's gender to being the girlfriend who is

concerned for her boyfriend in Tokyo during the attacks rather than the male

hero, the characters from the original story Kaori and Tadashi switching places

with Kaori the one we follow rather than the other way around. This is a change

which may actually be the one virtue the anime has over the original manga as,

while it's still a great book, the idea that Kaori, who is originally a damsel

who is drastically different in personality and is part of a plot point that becomes a plight for

Tadashi, is changed into a passive heroine here is a nice little change which alters

a great damn deal of the tone as a result.

Other changes are mostly in the

characters created for the film and their characterisation. The main heroine is

surrounded by two female friends who get a slice of the screen time. One is the

stereotype of the nerdy, shy girl but she at least gets to be involved with one

of the manga's more memorable images. The other is unfortunately the stereotype

of the glamorous young woman who sleeps around, one whose only possible reason

for existing as she does in the anime is so that the depiction of a sex act

with three people (discretely shown) that would usually only be seen in live

action porn can be written in; she as a depiction is the one real blot in the

adaptation which stings as, while he uses stereotypes, Ito even when he has sexually explicit moments or female characters

as monsters was always more tasteful even in the tasteless, preferring either

the truly alien, likable characters, sympathetic monsters or those with his

trademark madness projected from their wild bulging eyes.

Thankfully the choice of a female

protagonist is treated with the respect it deserves as a radical change, where

even thought she shows signs of the events happening around her hurting her,

including breaking down and crying like a child when stopped by military

personal from reaching a place, she's able to eventually accept the fate of

what is likely the end of humanity around her. It also means that, when in the

manga originally it's the boyfriend who had to deal with a longer plot line

involving her being drastically changed physically that he has to cope with,

the shorter take here with her having to deal with it really changes the way

the story goes. It may come off as crass to say this, but considering the

stereotypes of girlfriends that can be found in horror in any language of being

a mere damsel, simply changing the gender of the person we follow, not even

taking account the effect depicting them as gay or bisexual, can alter the span

of a story if, following a heterosexual woman, the one in peril she has to find

is her boyfriend. Followed here by a male photographer wanting to learn the

truth of the outbreak, a new side is shown that nicely mirrors what Ito does in the manga where its Kaori

having to feel the grief of what happens rather than the boyfriend having to

feel grief for what happens to Kaori.

In terms of adapting the manga in

general Gyo does have to truncate

the plot and bring the story up-to-date from 1999 to the 2010s, the internet

and YouTube (implicitly described) playing a great sub textual part in how it

both informs the public but proves to be useless against the natural threat. The

film manages to create an appropriately destroyed, abandoned cityscape where

the streets are only populated by monstrosities, filling this with a fully

fleshed-out narrative which manages to cover a great deal in only seventy

minutes or so, quite a feat which the anime has to be applauded for despite its

flaws in some of the priorities in storytelling. It even manages to include the

circus segment of the original manga - a strange tangent where, in the middle

of the end of the world, people have taken infected members of the public and

turned them into an attraction in a circus of decay - without feeling like its

missed the important plot points it has to deal with to make sense. The result

of this economic storytelling as well is that, fitting the work its adapting,

it develops its own idiosyncratic quirks that would make Ito proud, all the while avoiding what happened with the live

action Uzumaki film, which was

longer in length, in having to abruptly end with no real climax that used still

shots of events it sadly didn't depict.

Technically the only issue to be

found with Gyo is that, using 3D

animation for the aquatic monstrosities at times, the glaring difference

between 3D models and 2D animation can be spotted, a common issue still with

many anime, only with sharks with mechanical legs sticking out like a sore

thumb. Altogether it's an impressive production in terms of trying to adapt a

source that could've immediately become too absurd in motion, not only

succeeding in adding the menace that is in Ito's

work alongside clear absurdity but also making itself stand out as having its

own personality alongside the original source. Sadly its likely to be neglected

with the otherwise superior original comic, but as adaptations go particularly

in the barren area of horror anime, its commendable as an example which feels

suitably unique rather than lacking in comparison to manga.

==========

1

As of this review being published, we might be getting Tomie by Christmas in a deluxe set, pleasing me greatly. As for any

of the live action adaptations made in Japan, if I could see any they might

appear on the site even if they have no connection to anime.

2 This is a common trait of Japanese horror manga I've cherry

picked that I've grown to admire even if at times I worry I'm becoming

desensitised to material that would cause others to puke. Currently, the day

this footnote was created, I am going through the first omnibus volume of Franken Fran (2006-12) by Katsuhisa Kigitsu, a work that deliberately

steps over the line in terms of good taste from the beginning with grossly

depicted body horror in the panels. As much as I fret that this type of

material is too gross at points, too transgressive to the point of merely being

offensive and crass, like with Ito I also

realise the discomfort their imagery cause if probably more morally appropriate

for horror storytelling and also more important in getting gut reactions out of

people and forcing them, through the usually great illustration of Japanese

manga, to look at their own sack of bones and flesh they call their own body

with greater thought.

No comments:

Post a Comment