|

| From https://static.tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pub/ images/Gravion_1126.jpg |

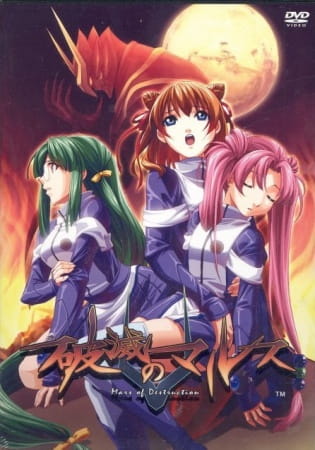

Director: Masami Ōbari

Screenplay: Fumihiko Shimo

Voice Cast: Haruna Ikezawa as

Runa Gusuku; Houko Kuwashima as Leele; Jun Fukuyama as Toga Tenkuji; Kenichi

Suzumura as Eiji Shigure; Mai Nakahara as Eina; Yuu Asakawa as Mizuki

Tachibana; Hikaru Midorikawa as Raven; Sho Hayami as Klein Sandman

Viewed in Japanese with English Subtitles

The giant robot/super robot anime

was 1963's Tetsujin-28, an

adaptation of Mitsuteru Yokoyama's

1956 manga Tetsujin 28-go. The

concept which has become a stereotype and large part of the aesthetic of anime

in general, giant robots fighting each other or monsters, would however be

properly solidified in the 1970s when manga author Go Nagai created Mazinger Z, which was a manga and first adapted

into anime in 1972. Over the next few decades new aspects would be created

within the genre - Mobile Suit Gundam

(1979-1980), whilst initially not successful, would eventually generate

into a cultural institution alongside bringing more adult "realistic"

world building, whilst Neon Genesis

Evangelion (1995-6) in the nineties would bring further psychological

depth, alongside countless other shows that'd develop and further sub-genres

and styles within this type of story.

At some point, however, giant

robots no longer were a major genre in the sense of selling for children - the

seventies shows were as much to sell toys to children, and when they weren't

the target audience it had to become the children who grew up into adults,

which is why we'll get into the prominence of "fan service". That

term has been used to denote sexual content, but "fan service"

generally means something to appeal to fans, including references to other

anime/manga or anything to denote nostalgia, all the types discussed to be

brought up with Gravion. This is

important as, in the 2000s, after a crop of post-Evangelion work trying to ride its wave of success, you started from

the nineties too to have throwbacks to the older type of robot shows but meant

more for adults. Eventually you'd also have Gurren Lagann (2007), a studio Gainax

work which was arguably at the time the one giant robot show which has a

greater audience appeal, but was openly taking inspiration from the old style

of the genre rather than Evangelion's

dark psychological tone. In the middle of this is Gravion, which immediately denotes which side of the fence it is

as, bright and vivid, it's a tale of a squad of pilots who fight monsters every

week, scored by JAM Project, a group

whose existence in anime is to score mecha programmes. When they have a lyric

here in the transformation scene of "soldier of soldier", immediately

it tells you from the first episode this is a deliberately broad and bombastic

show.

It's befittingly the directorial

work of Masami Ōbari, a figure who to

give him his due credit is a highly regarded animator and character/mecha

designer. Ōbari's directorial career on

the other hand is a weird and polarising one sadly; immediately recognisable

for his idiosyncratic character designs, (lithe figures, exaggerated curves on

female characters, pronounced noses etc.), which could however put people off,

he nonetheless started off with fan favourites like two episodes of Bubblegum Crisis (1987-1991), Detonator Organ (1991) and the 1994

Fatal Fury film.

It is by 1996 where his work gets

divisive and also not liked. I can attest to Voltage Fighter Gowcaiser (1996), an adaptation of an obscure Neo

Geo fighting game, and Virus Buster

Serge (1997), one of the first TV series Manga Entertainment released in the UK, being ridiculous. At the

point he helms Gravion, the first

series in this giant robot throwback series, he's already in his period of

directing hentai anime like Angel Blade (2001-2003), which is another irony

knowing that, in the 2000s on, one of the ways to sell these giant robot shows

to a wider audience was to increase the sex appeal, with a lot of fetishes

clearly chosen for this 2002 series to please potential otaku.

Having not watched a lot of this

genre, I have however developed enough knowledge of how this old school type of

mecha show, not the realistic ones or the likes of Gundam, practically embrace their clichés, be it the elaborate

transformation sequences to a plot about a piece of an enemy controlling the

robot I remember appearing in Mazinkaiser (2001-2), a spin-off Go Nagai project for OVA. Here in Gravion, in the first episode, a mysterious billionaire named Sandman

informs the global government of the planet that not only is there an oncoming

alien invasion but, since no one believes him, he's thankfully prepared a giant

robot powered by the mysterious energy of gravity to face them, piloted by

denizens living in his giant floating castle. Be it Toga who grew up there, or Luna

who was orphaned, everyone has a special trait that allows him or her to

undergo the stress of piloting each of the vehicles that form the ultimate

Gravion robot. One last member needed to pilot one of the legs is Eiji, who

comes to the castle the night of this announcement to locate his missing older

sister Ayaka, only for Sandman to have deliberately gotten him there to join

the team through this, the mystery of his older sister enough to keep Eiji on.

From there it's, as mentioned, a

monster of the week series, brightly coloured and with a lack of pretence which

is charming. The show's simple, the characters archetypes that bicker, bond and

want to protect the planet, even though there are details which are drip fed

throughout. Secrets are revealed, and in probably the make and break aspect of Gravion, its arguably a prologue, as Gravion (whilst it took two years to

appear) would have a sequel which finished the series called Gravion Zwei. Sequel series are a

curious thing for me as, in most cases, a lot of anime is one show, or has over

fifty episodes is required for big scale work; some major franchises have

multiple sequel series, which I have rarely watched even in leisure, and there's

the issue, for this case, that whether you have a show which tells its story

over a pair of series that anime's spotty history in terms of availability can

be a nightmare. This poses a problem if, like me, that meant having to try to

track down that sequel series for the whole story including major plot details;

bizarrely, in a growing file of strange decisions ADV Films made before they went in the red financially, they only

released the first season in the United Kingdom, so its notable this review is

entirely going to be about the first season only.

|

| From https://ai.fancaps.net/galleries/Gravion/ ep04/Gravion_Screenshot_0260.jpg |

Immediately in the first episode the influence of trying to sell the series is felt in how Sandman's home is populated by maids, woman and young girls, including very young girls, which might be innocuous but has to be in mind, even if its kawaii (cute), such iconography is a fetish that grew in the decades for otaku. As you read that piece, that detail is understandably going to make many of you uncomfortable to consider. This is where I myself admit my discomfort with it too. Some of it is the usual absurdity - that the oldest pilot of the Gravion robot, Mizuki, has (and I apologise for the crassness) a Double F bust size which is comically emphasised by even her personal fighter plane seat involving her leaning over - but I could've done without the jokes of young (underage) maids constantly stripping Eiji naked for medical checks.

It thankfully never becomes the

main point of the show, and at least we also got Cookie, a character I wish we

had more of, the main maid who is an adult woman and, in this world, is so

absurdly super strong she can carry five people, only one a child, on her own

shoulders in the middle of a city wide evacuation. The rest is just, from the

context, what was forced onto the production, as interestingly this is a female

dominated show where said female cast are quite strong. There are only two male

pilots of the robot, and even the techs, despite still wearing maid costumes,

are women in Sandman's entourage. There are stereotypes, such as Luna having a

love-hate relationship with Eiji, but Mizuki is revealed to have a back-story,

in spite of her hyper sexualised character design, of being very intelligent

and the friend of Eiji's older sister and no one is also incompetent. The one

character, the shy glasses wearing pilot Eina, who gets flustered in fights is

also painted as such without it becoming demeaning. So yeah, it is very odd

that the show was stuck with some of the fan service of a sexual kind baring

the usual sex comedy hijinks, the sign of how these giant robot shows were

stuck having to do this in spite of strong female characters.

Not a lot is delved into in terms

of the characters in general, their world almost entirely the castle and

fighting robots. A lot of major plot points clearly will appear in Gravion Zwei, but titbits are given -

we meet Leele, a mysterious shy girl hidden away in one of the towers in

Sandman's castle, Mizuki has an episode dealing with her relationship to Ayaka,

and we have an episode in Luna's home of Okinawa, which proved a great episode

altogether for world building and comedy. The world Eiji left, alongside his

conflict of whether to be part of this group, becomes the crux of the finale,

which does end the series on a conclusion of some sort. It's here that the

obvious issue, not the series' fault, that having two different seasons which

were released separately will prove an issue if you cannot track Gravion Zwei down, such as when another

throwback to giant robot anime which was openly inspired by Batman: The Animated Series (1992-5), The Big O had its 1999-2000 series and

a 2003 series but only the first ever released in the UK on DVD. These are old

series now, and realising how long it took to even get the second series

finally produced, Gravion as a first

season feels like merely the build, perversely like a nineties OVA which was

without a conclusion and meant to sell the manga as a result.

Animation wise, it's okay,

notable a studio Gonzo show. Gonzo were another trend of the 2000s,

starting properly as an animation studio making its own shows in 2000, being

prolific throughout the 2000s, and thus a huge part of my life getting into

anime in the early 2000s, before finding both financial problems and their

notoriety for the erratic quality of their productions maiming them in the late

2000s. Nowadays they are a shell of their former shelves, even if they are

still in business, no longer the polarising love-hate animation studio making a

lot of noise in the early to mid 2000s.

If anything, my take from Gravion were its little pleasures. The

mecha designs - held between Jin Fukuchi,

Kunio Okawara, Masami Obari himself, Yasuhiro

Moriki and Yousuke Kabashima -

stand out as they should, JAM Project and

everyone in the musical department providing appropriate rocking/bombastic

music for this material. Even the fact that the monsters in this show are

closer to the Evangelion

"angels" is at least an idiosyncratic touch to. The strong female

cast, in spite of its tone, is a compliment as is whenever the show has knowing

winks to its over the top nature - particularly whenever Sandman, played as

ultra serious despite his bombastic nature, becomes aware of it (bombastic

proclamations during the giant robot transformation or just going to the

beach), whilst his male second-in-command Raven eventually becomes the put-upon

and disgruntled employee. It's cool that

the stereotypes do get undercut, and how, in terms of this being a giant robot

show, its touches are novel, like a rocket punch which involved the pilot

having to steer the fist into the monster herself, which is cool, alongside

possibly the most logically way of getting said arm back in the physics of this

world that has to be praised just for the fact someone actually thought about it.

There is now a sense, annoyingly,

of both a lot to potentially like here, enough that I really enjoyed the show,

but that, even if you can see the second season, it just takes one bad creative

decision to mess the expectations up set by the first season. That's another

issue whenever sequel series are a possibility, as attested by people, since I

referenced it, that didn't like the second Big

O series. Gravion itself has

plot points - the mysterious figure, new characters introduced halfway through,

and the season arch about Eiji, with the additional subplot that the global

government trying to get involved, ending with a great cruel punch line for the

final episode. But it leaves many cards on the table un-flipped, and God help Gravion Zwei if it had a joker in the

deck. There's definitely the ominous sense that, after this and the porn, Ōbari's only other major work was a

couple more TV series up to 2011, where he hasn't been in the director's chair.

So I am left saying the Gravion was definitely

pleasurable and fun whilst it lasted, but Gravion

Zwei's another review entirely that could vary wildly.

|

| From https://i.ytimg.com/vi/pxnp1DX7GhY/hqdefault.jpg |