Director: Kunihiko Ikuhara

Screenplay: Yōji Enokido

Based on the manga by Chiho Saito

and the Be-Papas

Voice Cast: Tomoko Kawakami as

Utena Tenjou; Yuriko Fuchizaki as Anthy Himemiya; Aya Hisakawa as Miki Kaoru;

Kotono Mitsuishi as Jury Arisugawa; Kumiko Nishihara as Shiori Takatsuki;

Mitsuhiro Oikawa as Akio Ohtori; Takehito Koyasu as Touga Kiryuu; Takeshi Kusao

as Kyoichi Saionji; Yuka Imai as Wakaba Shinohara

Viewed in Japanese with English Subtitles

Even into the 2010s, the United

Kingdom never got Kunihiko Ikuhara's

seminal 1997 series Revolutionary Girl

Utena as a release. MVM

nonetheless released the 1999 tie-in film as Revolutionary Girl Utena: The Movie. This film is a thirty nine

episode story condensed into less than ninety minutes, which does prove an

obvious issue for a first form of this franchise to see. I however am

externally grateful to them for this curious decision as I've now seen Adolescence of Utena, which eventually

doesn't become something under the series' shadow but something greater. The

result in just ninety minutes is a surreal one-off that ties Ikuhara's work, a franchise with a huge

significance for LGBT anime and manga fans, LGBT themes being discussed in a

major project in the series, and is tied to even Japanese avant-garde art and

the films of Shūji Terayama in some

of Ikuhara's creative choices.

Ikuhara, alongside likely

directing episodes of Teenage Mutant

Hero Turtles, cut his teeth in the anime industry through the Sailor Moon franchise, which is notable

as it deviated from the original Naoko

Takeuchi manga with the nineties anime franchise its own huge cultural

beast. Reolutionary Girl Utena was

his seismic powerhouse, let loose and still having a profound effect today, to

the point most people probably don't realise it's based on a 1996 manga created

as part of a circle involving him called the Be-Papas.

Trying to assess a full plot is

going to be an issue as this is a retelling of a series, but sticking to the

film's form alone, it can be boiled down to this: in a school existing out of

time, an ever shifting entity like a living M.C.

Escher painting, sword duels between students are taking place with the

prize for the winner being the "Rose Bride" Anthy, who is explicitly

for this film a figure who will be with the victor even in bed. The titular

Utena, a new female student, discovers about these duels and intervenes out of

indignation and by pure accident, having accidentally found a ring important to

her is a symbol of dualists, winning a duel when provoked and thus tying

herself and Anthy together.

You cannot talk about any Utena, even just the film, without

considering just how significant it was for LGBT fans as, ironically alongside Sailor Moon which had a lesbian couple

awkwardly dubbed as cousins in the American export, this is a love story about

two young women. Utena in this film is hostile and pining for a male friend,

but the romance between her and Anthy grows over the course of the film. It's

explicit in the film at the beginning what is intended in how Utena is

introduced in the first scene, very short pink hair and dressed in boy's

clothes, before their slowly growing romance blossoms and becomes the crux of

the narrative. A lot of people to this day speak of how much of a watershed

moment this franchise was, such as Erica

Friedman, a proud gay former publisher of yuri (girl's love) manga, a

writer on the subject, and who got to present Adolescence of Utena at the Frameline Film Festival in San

Francisco, the British LGBTQ Film Festival and the Tampa LGBTQ Film Festival

back in the early 2000s1.

Coupled with this, and still felt

profoundly even in this abridged version of the series, is the delusions and heteronormative

trap of fairy tales. The "prince" who rescues the princess as in old Disney films aren't good, either an

illusion or an unhealthy concept, the back-story

of Anthy with her brother having a dark, incestuous aspect as Ikuhara never pulls his punches in

dealing with adult subjects in bright colours, especially as this back-story is

elaborated on further in the television series. The only good prince is Utena

herself, who decided to become one even if she eventually reveals full length

feminine hair in contrast to her masculine dress. Set in an ever changing,

shifting fantasy school Utena whilst

beautiful to look at constantly reveals the artifice throughout, a place that

is an illusion that eventually crumbles in shadows and horrors.

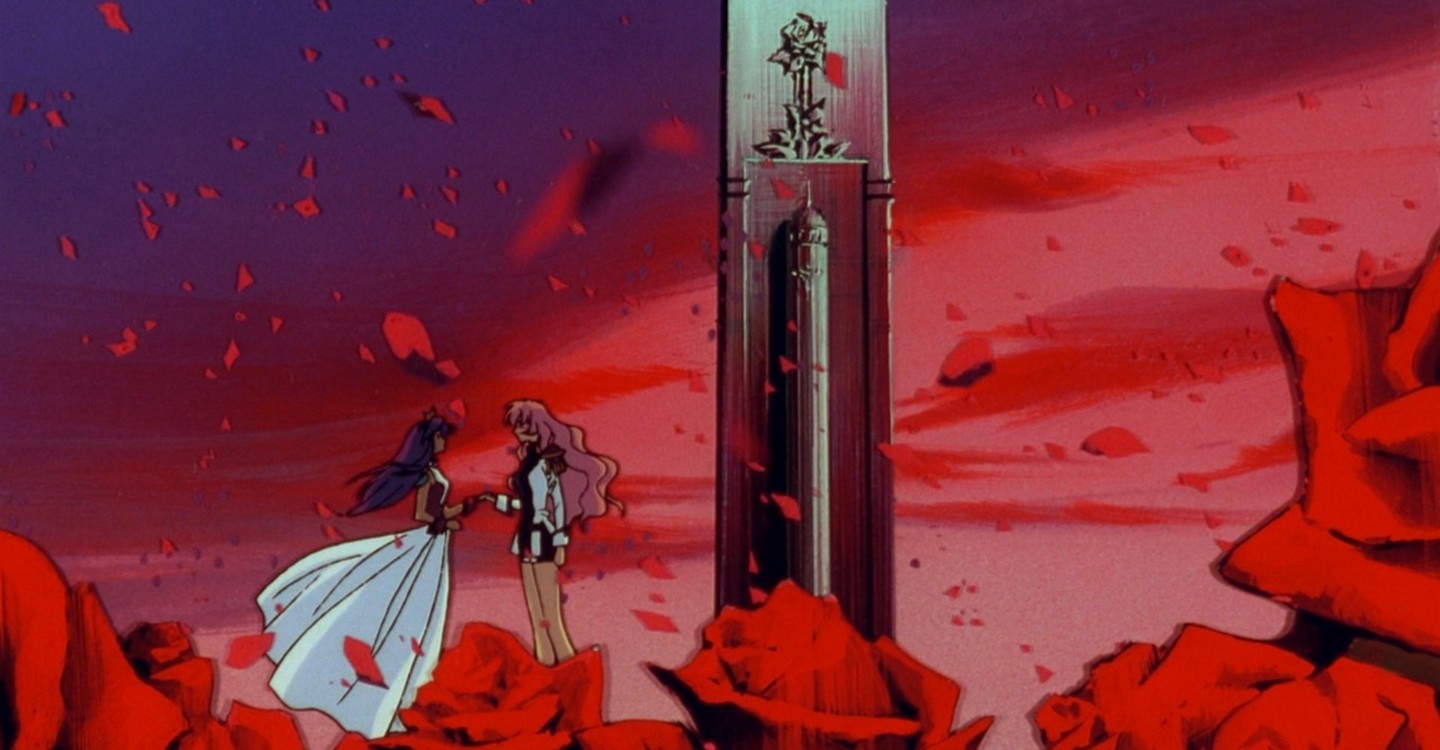

Significant to this is how

gorgeous this production is. Ikuhara

is someone I call "pop surrealism" because for me, the

"pop" is his use of bright colours, very clear symbolic motifs (roses

here) and the energy of his work that can juggle comedy to drama, such as the

abrupt cameo of a character Nanami but only in a gag segment as a cow stood

against very serious subject matter. This is the only theatrical film Ikuhara has made - a production even

co-produced with Sega, which is

likely explained with them collaborating on a 1998 Utena Sega Saturn game - and it's stunning to witness in the

quality and the early use of computer animation which thankfully gels.

Here it's notable how much Ikuhara was influenced by Japanese

avant-garde art. Probably one of the trademarks of this tale, found here, are

the silhouette girls, schoolgirls entirely as black shadows (without any

features) in school uniforms, who act as a Greek chorus, even acquiring a salacious

videotape involving Anthy and her brother. One of the most striking sequences,

when the leads fully connect, is literally staged on a pool supported on top of

a tower full of roses. The other pronounced choice is J. A. Seazer, an experimental composer whose trademark is combining

theatre and rock music who Ikuhara

explicitly hired for the television series to compose songs for. With his

trademark chorus singing to acid rock guitars, Seazer's only other anime contribution was to the notorious independently

made Midori (1992). Beyond this,

he's famous for his work in live action cinema with Shūji Terayama, the experimental filmmaker who is tragically under

seen and whose work clearly inspired Ikuhara

in hindsight for myself, productions like Pastoral:

To Die in the Country (1974) very much psychodramatic and surreal films

with bold visuals and choice of colour. The Seazer

music here, especially in the few duels seen, is exceptional as is the score by

composer Shinkichi Mitsumune.

Also of note is screenwriter Yōji Enokido, who deserves a lion's

share of the praise as, as I look into his career, whilst it is smaller than

other's he's made a career of idiosyncratic work. Penning the story for FLCL (2000) in particular on his resume

immediately suggests someone very comfortable with surreal and unconventional

storytelling, and considering he also penned the TV series, it's for the better

the person who worked on the TV series tried to compact this into a smaller and

more subjective piece.

Does the film actually work

though, especially as I have never seen the series? If we were talking about

just the first three-quarters, it's a gorgeous piece to watch, but a curiosity

only from Ikuhara. Things change

considerably in the final act, starting for me from a sequence in an elevator

involving water, which brings on from there and onwards a level of great

emotional relevance to the characters barely touched upon that cannot help but

over take me. Then the divisive final sequence happens, and Adolescence of Utena becomes

incredible. I cannot spoilt it, because just describing the scenes in a

sentence isn't the same as watching the finale as I have learnt thinking of

this film over the years, that a character is turned into a car and the final

act is a car chase to escape into the real world.

It is one of the most surreal

things I have witnessed, where even the mech animators hired were baffled infamously

why they were hired for a Revolutionary

Girl Utena film themselves. The result also happens to be one of the best

things to have been done in theatrical anime, an exceptional short in its own

length of animation, spectacle, emotional power and symbolic power. The car

metaphors in the film are strange but a) Ikuhara

has been quoted in being inspired by a craze for supercars in the seventies

which he viewed as a juvenile fantasy2, connectable to the dangerous

fantasy of fairy tales and found in the TV sereis, and b) there's loaded

symbolism in Anthy's brother and his madness which we eventually see being

connected to his desperate search for car keys, fearing if they cannot be found

the "car" will rust.

The finale is something to behold

when, if considered, the symbolism is simple and understandable with a

spectacular result. The leads must traverse the perils of a fairytale castle,

now a monstrous hundred wheeler that can crush cars underneath, to find

happiness. Even if happiness is in a literal wasteland, as it is no longer the

delusional fantasy, reality is found and the ending sequence turns the Adolescence of Utena beyond a curiosity

in Kunihiko Ikuhara's career, but a

crowning gem.

And thankfully, it has lasted.

This franchise is still held highly to this day, to the point that arguably

this work is just as monumental to anime in the nineties as Neon Genesis Evangelion and Cowboy Bebop (1998-9) are, the kind of

show that has been itself an influence, as can be attested to Stephen Universe creator Rebecca Sugar admitting this for her own

famous work3. At the time, this was followed by an absence from

Ikuhara in the industry, still working on other projects as well as in other

mediums, but never directing any titles throughout the 2000s. Thankfully, in

2011 we got Mawaru Penguindrum,

leading to a trilogy throughout the 2010s alongside Yurikuma Arashi (2015) and Sarazanmai

(2019). What the 2020s will lead to for him will be of interest and baited

anticipation. For myself, until the TV series itself, this is a pretty big

title in my own personal fandom to finally have seen, and by God did it exceed

expectations.

=========

1) HERE

2) "When I was little there was a supercar boom. Maybe because of that,

even now such a car is something that satisfies childish desires in the adult

world. A car seems like that sort of thing. As you grow up toys tend to

disappear quickly from your life. Even if, as a child you wanted a model of

robot, when you’re an adult these sort of things that you want seem to

disappear, isn’t that so? Well, you may want something like a house, but

obviously, it’s a little different from wanting a toy. My idea of a car is

something that is exceedingly close to an adult’s toy..." - "Be-Papas

Interview". Animage. 20 (1): 4–13. May 10, 1997. [Found HERE]

3) HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment